Thanks to the rise and popularity of crime dramas, podcasts, and documentaries, the average person has become much more knowledgeable regarding legal and investigative topics. One area that has been highlighted extensively in the media is that of false or coerced confessions that often occur within our judicial system. It was not that long ago that a confession was deemed to be “checkmate” in a criminal case. A defendant who had previously confessed, even if he or she later recanted their confession prior to trial, had little chance of being acquitted, despite the presence of exculpatory evidence in the case. But we now know that sometimes people do falsely confess to crimes they did not commit. This can happen for a variety of reasons. A factor often present in false confession cases is the criminal suspect being threatened with the death penalty by law enforcement officers. This half-a-century old wrongful conviction case is currently dealing with this precise situation.

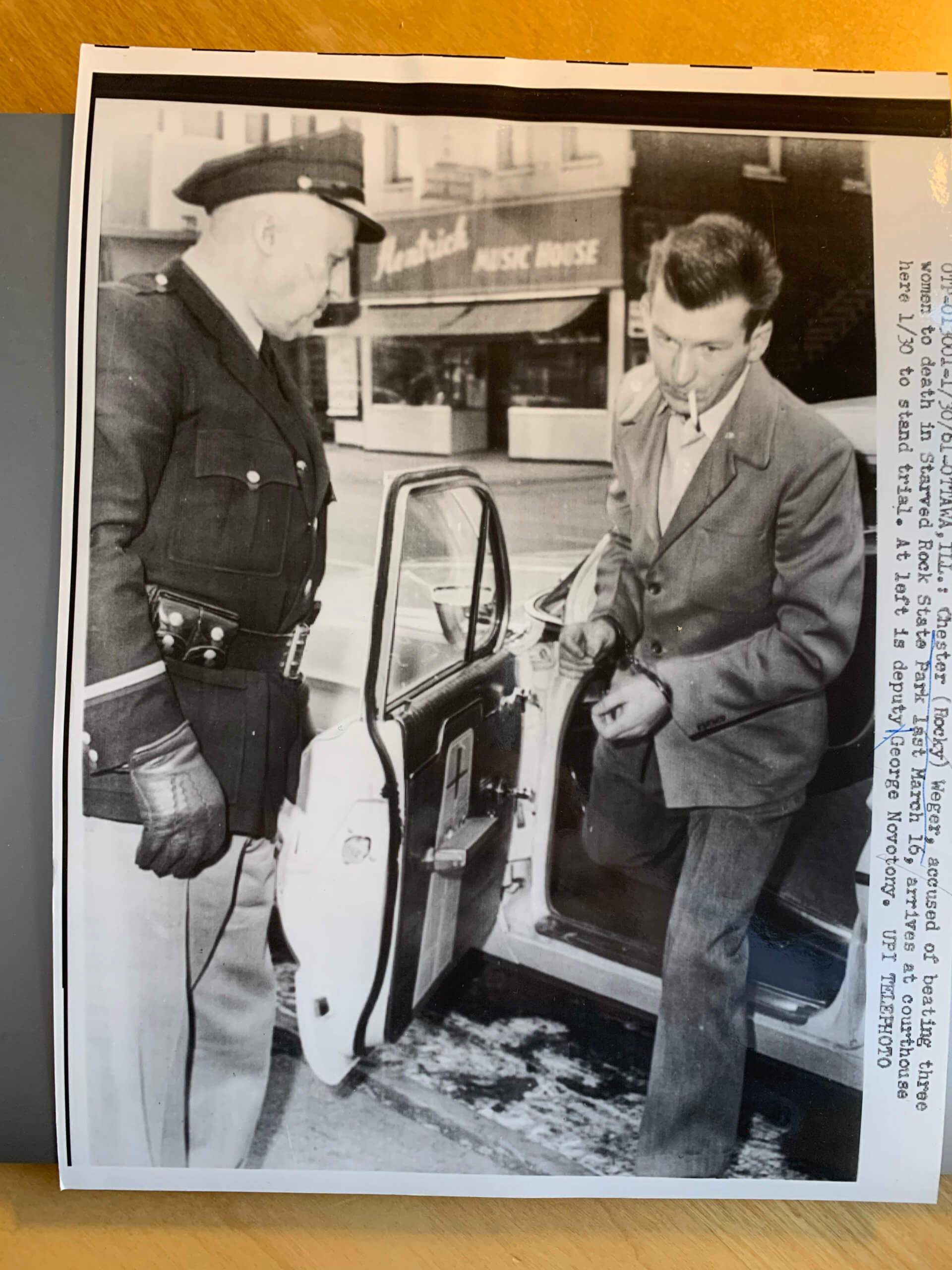

In March of 1960, three women were brutally bludgeoned to death in Starved Rock State Park in downstate Utica, Illinois. Despite the murders occurring in this small town, the case became a national news story. Eight months after the women were found slain, Chester Weger, a twenty-one-year-old dishwasher at the Starved Rock Lodge, confessed to the attacks. Prior to his trial, Weger recanted his confession and denied any responsibility for the horrible crimes. Six decades later, now 81 years old, Chester Weger has been released on parole and continues to seek to prove his innocence.

The Crime

On Monday, March 14, 1960, three Chicago women, Mildred Lindquist, 50, Frances Murphy, 47, and Lillian Oetting, 50, set out on what was to be a four-day vacation at the popular natural attraction: Starved Rock Park near Utica Illinois. After checking into the Starved Rock Lodge in the morning, the women had lunch and then went out for a hike in the beautiful St. Louis Canyon area of the Park. The women would never be seen alive again.

On Monday, March 14, 1960, three Chicago women, Mildred Lindquist, 50, Frances Murphy, 47, and Lillian Oetting, 50, set out on what was to be a four-day vacation at the popular natural attraction: Starved Rock Park near Utica Illinois. After checking into the Starved Rock Lodge in the morning, the women had lunch and then went out for a hike in the beautiful St. Louis Canyon area of the Park. The women would never be seen alive again.

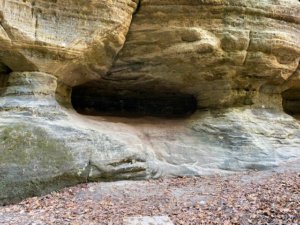

After several attempts to reach the women were unsuccessful on Monday evening and Tuesday morning, the women’s families became concerned. On Wednesday morning, after the women had still not been heard from, a search party was dispatched. A few hours later, the women’s bloodied and battered bodies were found inside a small cave in St. Louis Canyon. The women had been savagely beaten about the head and two of the victims were naked from the waist down.

Despite the women’s semi-naked condition, an autopsy concluded that the women had not been sexually assaulted. Investigators saw no apparent robbery motive either, as the women’s watches and jewelry were not taken. A frozen tree limb found nearby was thought to be the murder weapon.

Who is Chester Weger?

At the time of the murders, Chester Weger was a 21-year-old dishwasher at the Starved Rock Lodge. He testified that he was on a break alone in a room at the Lodge at the time the women were allegedly murdered. Weger was a husband, a father, and a veteran who became known as Illinois State’s longest incarcerated inmate, also infamously known as the “Starved Rock Murderer.”

View Photos from the Chester Weger Case

The Events Leading Up To The Confession

In the days following the discovery of the women’s bodies, Chester Weger was among those who were questioned by investigators with the Illinois State Police. Chester was interrogated again about a month later by Illinois State Police investigators. Chester passed all of these polygraph examinations. In late September, about six months after the women were found murdered, Chester was picked up by LaSalle County Sheriff’s Deputy William Dummett and driven to Chicago for the administration of another polygraph test. Chester was interrogated throughout the day. Deputy Dummett claimed that Chester had failed the test and attempted to persuade Chester to admit guilt but Chester maintained his innocence. On the drive back to Chicago, Deputy Dummett repeatedly threatened Chester that if he did not sign a confession, he would be sentenced to the electric chair. Shortly thereafter, in October, the Illinois State Police assigned teams of troopers to conduct continuous surveillance of Chester and he began to be followed by the Illinois State Police. This constant surveillance continued for over a month. On November 16, 1960, Chester was picked up by LaSalle County authorities for purposes of questioning him yet again. Chester was interrogated for hours but continued to maintain his innocence. Later that night, despite the fact that there was no physical evidence linking Chester to the crime, no witnesses had placed Chester at the crime scene, and Chester was maintaining his innocence, warrants were issued for Chester’s arrest. Chester was placed in a lineup regarding a robbery that had occurred at Deer Park and a rape that had occurred at Deer Park in 1959. Chester was then interrogated yet again. Chester was told that if he did not confess, he would be sentenced to the electric chair. The interrogation lasted late into the night. After having been kept awake by authorities and repeatedly interrogated in September over a twenty-four hour period, after having been tailed by Illinois State troopers for nearly two months, after having been threatened by LaSalle County Sheriff’s Deputy William Dummett that if he did confess he would receive the electric chair and “ride the thunderbolt,” after having been served with warrants for murders that he had steadfastly maintained for eight months he had not committed, after having been brought to the courthouse on November 16th and interrogated off-an-on for an eight hour period, Chester Weger, shortly before 2:00 a.m., on November 17, 1960, gave Deputy Dummett a confession.

In the days following the discovery of the women’s bodies, Chester Weger was among those who were questioned by investigators with the Illinois State Police. Chester was interrogated again about a month later by Illinois State Police investigators. Chester passed all of these polygraph examinations. In late September, about six months after the women were found murdered, Chester was picked up by LaSalle County Sheriff’s Deputy William Dummett and driven to Chicago for the administration of another polygraph test. Chester was interrogated throughout the day. Deputy Dummett claimed that Chester had failed the test and attempted to persuade Chester to admit guilt but Chester maintained his innocence. On the drive back to Chicago, Deputy Dummett repeatedly threatened Chester that if he did not sign a confession, he would be sentenced to the electric chair. Shortly thereafter, in October, the Illinois State Police assigned teams of troopers to conduct continuous surveillance of Chester and he began to be followed by the Illinois State Police. This constant surveillance continued for over a month. On November 16, 1960, Chester was picked up by LaSalle County authorities for purposes of questioning him yet again. Chester was interrogated for hours but continued to maintain his innocence. Later that night, despite the fact that there was no physical evidence linking Chester to the crime, no witnesses had placed Chester at the crime scene, and Chester was maintaining his innocence, warrants were issued for Chester’s arrest. Chester was placed in a lineup regarding a robbery that had occurred at Deer Park and a rape that had occurred at Deer Park in 1959. Chester was then interrogated yet again. Chester was told that if he did not confess, he would be sentenced to the electric chair. The interrogation lasted late into the night. After having been kept awake by authorities and repeatedly interrogated in September over a twenty-four hour period, after having been tailed by Illinois State troopers for nearly two months, after having been threatened by LaSalle County Sheriff’s Deputy William Dummett that if he did confess he would receive the electric chair and “ride the thunderbolt,” after having been served with warrants for murders that he had steadfastly maintained for eight months he had not committed, after having been brought to the courthouse on November 16th and interrogated off-an-on for an eight hour period, Chester Weger, shortly before 2:00 a.m., on November 17, 1960, gave Deputy Dummett a confession.

After his arrest, but prior to his criminal trial, Chester recanted his confession, claiming it was the product of police threats and pressure. Despite testifying in his own defense, and the fact that there was no physical evidence linking Chester to the bloody crime scene, the jury found Chester guilty but refused to impose the death penalty.

Timeline:

11/16/60 Chester Weger is arrested

11/17/60 Chester Weger confesses to the murders

11/19/60 Chester Weger recants his confession

01/20/61 Criminal trial commences

02/27/61 Chester Weger testifies in his own defense

03/03/61 The jury finds Chester Weger guilty

04/03/61 Chester Weger is sentenced to life in prison

The Legal Backdrop

Significantly, Chester Weger’s trial took place prior to two landmark Supreme Court decisions that issued just a few years after his conviction. In 1963, the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963), which held that the prosecution must produce to the defense all potentially exculpatory evidence, in other words evidence that is favorable and might exonerate the defendant. What this means is that at the time of Chester Weger’s trial, unlike today, the prosecutors were under no obligation to turn over favorable evidence to the defense. For example, if the prosecutors possessed evidence that implicated someone else, they had no legal duty to provide that evidence to Chester Weger and his attorney.

In 1966, the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), which held that detained criminal suspects, prior to police questioning, must be informed of their constitutional right to an attorney and against self-incrimination. Had this decision been the law in 1961, the Sheriff’s deputies would not have been allowed to question Chester without providing him with these legal warnings. More importantly, had Chester asked for an attorney, the Sheriff’s deputies would not have been permitted to interrogate Chester and he would never have confessed.

Factors Favoring Chester Weger’s Innocence

There are numerous factors that cast doubt on Chester’s confession and support his case of innocence. At the outset, there is no physical evidence linking Chester to this gruesome crime scene and no witnesses place him at the scene of the crime. However, there is physical evidence that supports Chester’s exoneration. A blond hair found on the finger of Frances Murphy’s glove was analyzed by the Eastman Kodak company and found to be dissimilar to hair samples taken from Chester. Black hairs were also found in the palm of Lillian Oetting. Chester did not have black hair, so those hairs could not have come from him. Although numerous hairs and fibers were collected and analyzed, no hair or fiber evidence was introduced at Chester’s trial. The fact that both blond and black hairs were recovered on the victims strongly suggests the presence of two killers. It is also unlikely that the 5’8” Chester Weger would be able to overpower and restrain all three women.

Chester passed several polygraph examinations in the weeks after the murders. There was no reason to give Chester yet another polygraph examination six months later and authorities claim that Chester failed this exam must be looked at quite skeptically.

Chester’s claim that is confession was involuntary and coerced is supported by the fact that Sherriff’s Deputy Dummitt threatened Chester Weger with the electric chair if he did confess. The threat of death is one of the leading factors contributing to false confessions. Moreover, Chester’s confession is implausible on its face. Chester claims that his motive was robbery, yet when the bodies were found, the women still possessed their jewelry and rings. It also defies common sense that one of the women would have started the altercation by attacking Chester, as stated in the purported confession.

Decades after Chester Weger was convicted, a juror admitted to the Tribune in 2016 that she found Weger’s confession “implausible” at the time. Weger’s current attorneys, Andy Hale and Celeste Stack, argue that a case such as this would have never made it to trial under today’s standards.

Around 1982, an alleged deathbed confession was made from an anonymous woman from her hospital bed to a Chicago police officer. An affidavit recounting the event surfaced in 2006. Sergeant Mark Gibson states that he went to a hospital to help the woman “clear her conscience.” The woman told the officer “things got out of hand” at a State Park and “they dragged the bodies.” Gibson reported that this confession was cut short by the woman’s daughter, who said her mother was not of sound mind. Could this incident be referring to the Starved Rock Murders?

Throughout his incarceration, Chester Weger continued to plead his innocence. In a letter to the Chicago Tribune on April 20, 1963, Weger wrote, “Now there’s nothing in the world that I needed bad enough to kill for.” His friends and family rallied behind him in 2013 starting a “Friends of Chester Weger” Facebook page with almost two thousand followers. Again, in 2016, he told the Tribune that he would rather die in prison than admit to something he did not do. Along with his fight to prove innocence, Weger sought clemency but was denied in 2007.

Chester Weger’s Release

On November 20, 2019, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board, in a 9-4 vote, granted Chester Weger’s request for parole. The prior twenty-three requests had been denied. At the time of his release, Chester Weger was the second-longest serving Illinois inmate, having been incarcerated for 61 years. Chester Weger’s attorneys, Andy Hale and Celeste Stack, were thrilled at Chester’s release from prison and vowed to continue Chester’s fight to prove his innocence.

On November 20, 2019, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board, in a 9-4 vote, granted Chester Weger’s request for parole. The prior twenty-three requests had been denied. At the time of his release, Chester Weger was the second-longest serving Illinois inmate, having been incarcerated for 61 years. Chester Weger’s attorneys, Andy Hale and Celeste Stack, were thrilled at Chester’s release from prison and vowed to continue Chester’s fight to prove his innocence.

“We are very pleased that Chester was released today into the arms of his devoted family, who have waited decades for this day.” lead counsel Hale tells ABC7 news.